The War on Russia in its Ideological Dimension

The war against Russia is currently the most discussed issue in the West. At this point it is only a suggestion and a possibility, but it can become a reality depending on the decisions taken by all parties involved in the Ukrainian conflict – Moscow, Washington, Kiev, and Brussels.

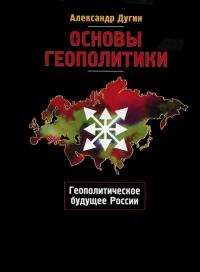

I don’t want to discuss all the aspects and history of this conflict here. Instead I propose to analyze its deep ideological roots. My conception of the most relevant events is based on the Fourth Political Theory, whose principles I have described in my book under the same name that was published in English by Arktos Media in 2012.

Therefore I will not examine the war of the West on Russia in terms of its risks, dangers, issues, costs or consequences, but rather in an ideological sense as seen from the global perspective. I will therefore meditate on the sense of such a war, and not on the war itself (which may be either real or virtual).