When Russian Eurasianism Meets Turkey’s Eurasia

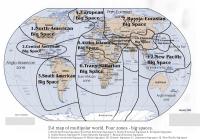

This is the story of an idea. The political concept of Eurasia, or “Eurasianism,” refers to the spiritual linking of the European and Asian peoples in the history and future of Russia. The idea behind the Eurasia movement derives from the works of Prince N. S. Trubetskoi, P. N. Savitski, G. V. Vernadski, and several others. Trubetskoi believed that the inter- connection of Eastern Slavs and the Turkic and Uralo-Altaic steppe peoples — or Turanian peoples — is one of the main building blocks of Russian history. In the 1920s, this theoretical concept found many followers among Russian émigrés dispersed in Poland, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Germany, France, and Czechoslovakia who were searching for a new theory to combat the ideological thrust of the Marxist- Leninist revolution in Russia. A small “Eurasianists” movement developed, yet Eurasianism put down only weak roots and rapidly declined.

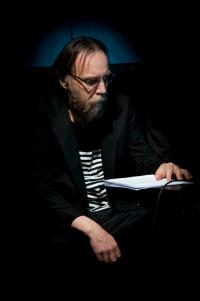

Neo-Eurasianism, inspired by the earlier movement, gained traction and considerable popularity in Russia during the years leading up to and following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Lev Gumilev, often cited as the founder of the Neo-Eurasianist move- ment, developed a theory of ethno- genesis holding that the peoples of the Eurasian steppe included not just the Russians but also the Turkic peoples of Central Asia. Gumilev regarded Russians as a “super-ethnos” kindred to Turkic peoples of the Eurasian steppe, including the Tatars, Kazakhs, and even the Chingizid Mongolians. With this theoretical synthesis, Gumilev and his followers concluded that Russia is not a natural part of “the West,” that it is instead culturally closer to Asia than to Western Europe. Neo-Euransianism thus resonates with many Russian intellectuals and politicians who fear the West and are divorced from its values.