Russia

Dugin Calls on Journalists in CIS to Develop a Unified Cultural Media Code

The Imperative of Russian Power

On the question of the Ideology

The Hermeneutic Circle of Russian Victory

Only War Determines What Exists and What Does Not

Winners are not judged. Everyone else is. The only exception is made for winners. For our truth to prevail — in both the grandest sense (civilizational, philosophical, religious) and the smallest (simple facts like shelling, casualties, invasions, attacks on nuclear facilities) — we must, at the very least, win.

A Call for a New Russian Society

RUSSIAN JUCHE

The Phenomenon Of War: Metaphysics, Ontology, Boundaries

We will not be able to understand the full depth of the current confrontation without philosophical reflection. Philosophers have always interpreted war as something necessary. Heraclitus speaks of war as the "father of things": πόλεμος πάντων μεν πατήρ εστί, πάντων δε βασιλεύς. War has always constituted the world and space. Without war, without division, the world is impossible.

Traditionalists of all countries, unite!

Enlightening Society with Russian History

Living and acting in the spirit of the Donbass

The spirit of the Donbass is the realisation of the Imperium, it is a paradigm of undivided theoria and praxis, it is a model but even more a categorical and binding archetype for conceiving, planning, concretising and realising the ideological clash of the culture war, that Kulturkampf through which the Italian and European world too will know and will want to free themselves from the global and unipolar oppression of American hegemony.

Putin's oath to the future

Moscow Is a Front-Line City

Historical Phases of Russian Orthodoxy

The adoption of Orthodoxy by Vladimir, the Grand Prince of Kiev, marked the starting point of the Christian cycle in Russian history, which spans almost the entire history of Russia — with the exception of the Soviet period and the era of liberal reforms. This cycle represents a complex and multidimensional process, which would be inaccurate to describe as a gradual and unidirectional penetration of Orthodox-Byzantine culture into the folk environment, simultaneously displacing pre-Christian (‘pagan’) beliefs.

Total Militarisation

Militarisation means shifting society onto a military footing. The scale and main directions of militarisation are open to debate as they depend on the specific historical and geopolitical situation, economic capabilities and resources, political ideology, and cultural dominants. When a country is at peace and its vital interests and very existence are not threatened, excessive militarisation is unnecessary and superfluous.

One for all — to which country will our heroes return?

Everyone understands that on the fronts of the Special Military Operation (SMO), a new elite of Russia is being forged. This is the estate of bravery (Hegel), which is to reboot the state. It is clear that the war heroes at the front are already divided into future strata: pure warriors, commanders, inventors, creators, strategists, economists. Among them is also the forming estate of ideologists. A bright symbol of theirs was Vladlen Tatarsky; many today rally around the front-line philosopher Korobov-Latyncev.

A New Russian Worldview

Contemporary social science in Russia needs to catch up in understanding the changes occurring in the country and in forming a sovereign worldview, and it needs to be accelerated, philosopher Alexander Dugin told journalists at the 5th Congress of the Russian Society of Political Scientists in Svetlogorsk (Kaliningrad region).

Forward to the New Middle Ages!

In Russia, the year 2024 has been proclaimed the Year of the Family. Clearly, in this area, things are quite dire for us. The alarming rates of divorce, abortion, and declining birth rates represent a national catastrophe. If we take the Year of the Family seriously, relying on the classics (but not the liberal or communist ones, as they are likely to advise something that will only hasten the disintegration of the family), we should simultaneously return to our roots and take a step forward.

All-Russian Ideology Emerges at the Front

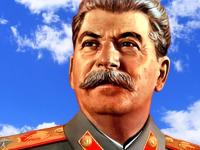

Certainly, there are those who voluntarily and consciously went to war, already possessing an ideology. There are the convinced rightists (Orthodox, monarchists, imperialists). There are the leftists (Stalinists, anti-globalists). There are left-rightists — National Bolsheviks. By the way, Prigozhin articulated, in many respects, exactly the left-right discourse — justice and strength.

Russian Ecclesiology: the stages of Russian Orthodox Historicism

The adoption of Orthodoxy by the Grand Duke of Kiev Vladimir was the starting point of Christian historicity, which covers almost the entire history of Russia - with the exception of the Soviet period and the era of liberal reforms. This historicity itself was a complex and multidimensional process, which it would be wrong to describe as a gradual and unidirectional penetration of Byzantine Orthodox culture into the popular environment, in parallel with the displacement of pre-Christian ('pagan') ideas. Rather, we are talking about different phases of the temporal synthesis between Byzantinism and East Slavic demetriac civilisation, phases determined by the different correlation of the main structures - Byzantine ideology at the elite level and the reception of Christianity by the people as such.

The Russian World and its Cathedral

End the Liberals: The People’s Hope for Change

Certainly most thinking individuals would agree that in the 1990s, the Russian state was taken over by adversaries who imposed external control over it – over our entire society. Its overarching name is liberalism. Not some ‘bad liberalism’, ‘distorted liberalism’, or ‘pseudo-liberalism’, but simply liberalism. No other kind of liberalism exists. Russian liberals became nodes in this occupation network.